The Seattle Pilots were the only team in Major League Baseball history to go bankrupt.

Part of a four-team expansion that also saw the debuts of the Montreal Expos, Kansas City Royals and San Diego Padres, the Pilots began in Seattle in 1969. The following year, the team moved to Milwaukee and became the Brewers.

In a year that saw Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid set records at the box office, Neil Armstrong become the first man to walk on the moon, the Beatles perform live for the last time and the Manson Family murder five people in cold blood, Seattle got big-league baseball. Just a year later they were gone, after going bankrupt and being bought by Bud Selig. “You go back a couple generations in baseball history and we had professional baseball from 1901 to 1969, through two World Wars and a depression, and then – poof! – it’s gone,” Seattle sports historian David Eskenazi said. “The first year we didn’t have pro baseball was 1970.”

Seattle initially had much going for it when it joined the American League in 1969. Long a hotbed for minor league baseball, the city was home to the Seattle Rainiers, one of the marquee franchises of the Triple-A Pacific Coast League. The Cleveland Indians had almost moved to Seattle in 1965, and Kansas City A’s owner Charles Finley considered Seattle before moving to Oakland in 1968. The third-largest metropolitan area on the West Coast [behind Los Angeles and San Francisco], the Emerald City had landed the expansion NBA SuperSonics just two years before the Pilots came into existence.

Four decades after losing the Pilots, Seattleites got another taste of how cold and ruthless professional sports can be, when Howard Schultz recklessly sold the Sonics to a group of Oklahoma City businessmen who moved the team to OKC in 2008.

Dewey and Max Soriano were the franchise’s majority owners. The brothers put up $2 million – two-thirds of it by Max – and had several partners investing smaller amounts. The Sorianos, who had both played locally, seemed perfectly suited to be Seattle’s first big league baseball owners. Dewey had served as general manager of the Rainiers and president of the Pacific Coast League. Max, who pitched well enough at Washington to make the Huskies All-Century Team, went to law school before becoming PCL legal counsel. The Sorianos knew baseball. What they lacked were deep pockets, a big-league ballpark, and full community backing.

As part of the expansion deal, MLB insisted the city build a new — preferably domed — stadium within three years.

The Pilots played in aptly-named Sicks’ Stadium, a minor league park named after brewery magnate Emil Sick, who had the stadium built in 1938. The 11,000-seat venue was decrepit, offering no built-in utilities for concession stands. Rife with plumbing issues, players were forced to take cold showers and water pressure was so low that stadium toilets often wouldn’t flush. Forced to retrofit the tiny Triple-A park with 15,000 additional seats before the start of the season, workers were still nailing and painting bleachers the day of the Pilots home opener. To make matters worse, ticket prices were among the highest in baseball.

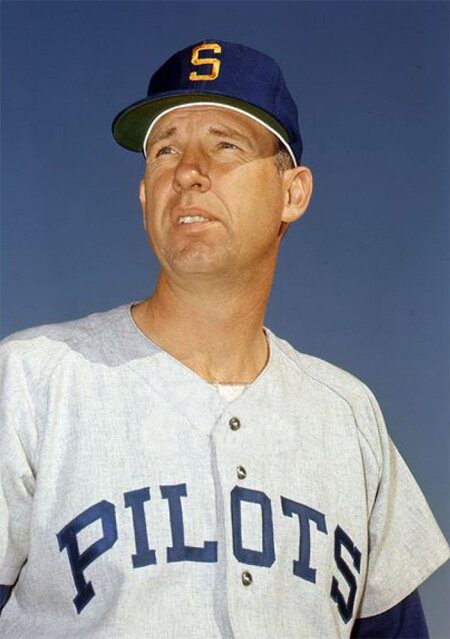

The team’s nickname came from Seattle’s involvement in the aeronautics industry. Long before Microsoft, Amazon and Starbuck’s started in the Emerald City, Boeing was king. The team colors were royal blue and gold, and they wore a pilot-like cap with the scrambled egg design across the bill. Joe Schultz, who had coached with three St. Louis Cardinal teams that won NL pennants but had never managed at the big league level, was named the Pilots first skipper. Schultz made Sal The Barber Maglie, the former New York Giant right-hander who led the NL in wins and ERA in the early 1950s, his pitching coach.

The Pilots obtained Lou Piniella from Cleveland in the 1968 AL Expansion Draft, then traded him to the Kansas City Royals one week before Opening Day in 1969. Sweet Lou went on to be named 1969 AL Rookie of the Year.

The 1968 American League Expansion Draft provided the Pilots with several bona fide big leaguers. The fleet Tommy Harper led the AL with 73 stolen bases in 1969, which still stands as the Pilots/Brewers record. Outfielder Tommy Davis, who won two NL batting titles with the Dodgers in the early

1960s, was obtained from Los Angeles. Don Mincher became the franchise’s first All-Star, and Seattle drafted two quality pitchers. Southpaw Steve Barber had thrown a no-hitter for the Yankees in 1967, while right-handed reliever Ironman Mike Marshall went on to win the 1974 Cy Young Award with the Dodgers.

On Tuesday, April 8, the Seattle Pilots won their first-ever game, 4-3, over the California Angels at Anaheim Stadium. They drew 14,993 for their April 11 home opener, a 7-0 win over the Chicago White Sox, but three days later only 3,611 watched the Pilots lose to the Royals. One April home game drew just 1,954. An August 3 date with the New York Yankees brought a franchise-record 23,657 to Sicks’ Stadium but, on Tommy Harper Night three weeks later, the speedy second baseman stole his 60th and 61st bases of the season before a mere 6,720.

Schultz kept the Pilots reasonably competitive in the first half of the season before a 9-20 July record led to their unraveling. Seattle scored 639 runs and allowed 799. Placed in the newly-formed six-team AL West, they went 64-98 to finish last, 33 games back of the division champion Minnesota Twins. The Pilots drew only 677,944, though that was more than the Phillies, White Sox, Padres or Indians [the major league average in 1969 was 1,134,569].

Not wealthy enough to support the Pilots, the Sorianos were forced to sell a 47 percent share of the team to former Cleveland Indians owner William Daley. By the end of the season, the franchise had run out of money. Bud Selig, a 35-year-old auto leasing executive and Milwaukee native, formed an ownership group intent on purchasing the Pilots and moving them to Milwaukee, which had lost the Braves to Atlanta in 1965.

In commemoration of the Pilots 50th anniversary of their first and only season, the Seattle Mariners wore the 1969 throwback uniforms in a game against the Baltimore Orioles on June 22, 2019.

In March 1970, the Pilots became the first team in MLB history to declare bankruptcy. One week before the season began and with the team’s finances in ruins, the Pilots fate was still so uncertain that when their equipment truck left spring training in Arizona, it stopped in Utah and awaited word on whether to continue to Seattle or head northeast to Milwaukee. Selig then bought the Pilots in bankruptcy court for $10.8 million [just under $70 million today]. On March 31, word came down to go to Wisconsin. The Pilots were moving to Milwaukee.

The new owners did not even have enough time to get new uniforms. They simply ripped off the Pilots name and logo and slapped Brewers across the chest. The state of Washington successfully sued the American League over the Pilots departure. The league agreed to give Seattle another expansion team in 1977: the Mariners. After the Pilots left, Sicks’ Stadium was used as a minor league park until 1976 before being demolished three years later. A Lowes Home Improvement store now stands on the site.

On this date in 1968, the expansion Seattle Pilots signed Jim Bouton, who had won 21 games with the Yankees in 1963 and 18 the following season. After an arm injury, he lost his fastball and was relegated to the minor leagues before trying to revive his career as a knuckleballer. Bouton went 2-1 with the Pilots and was dispatched to Triple-A Vancouver before being traded to the Houston Astros in August 1969.

Bouton, who died this past July at 80, kept a diary of the 1969 season, which was published as Ball Four the following year. An irreverent, best-selling book that angered baseball’s hierarchy and changed the face of sportswriting, Ball Four captured the humor, profanity, and pathos of a major league clubhouse with remarkable candor. Baseball historian Terry Cannon said Ball Four is “arguably the most influential baseball book ever written.”