“I try not to break the rules but merely to test their elasticity.”

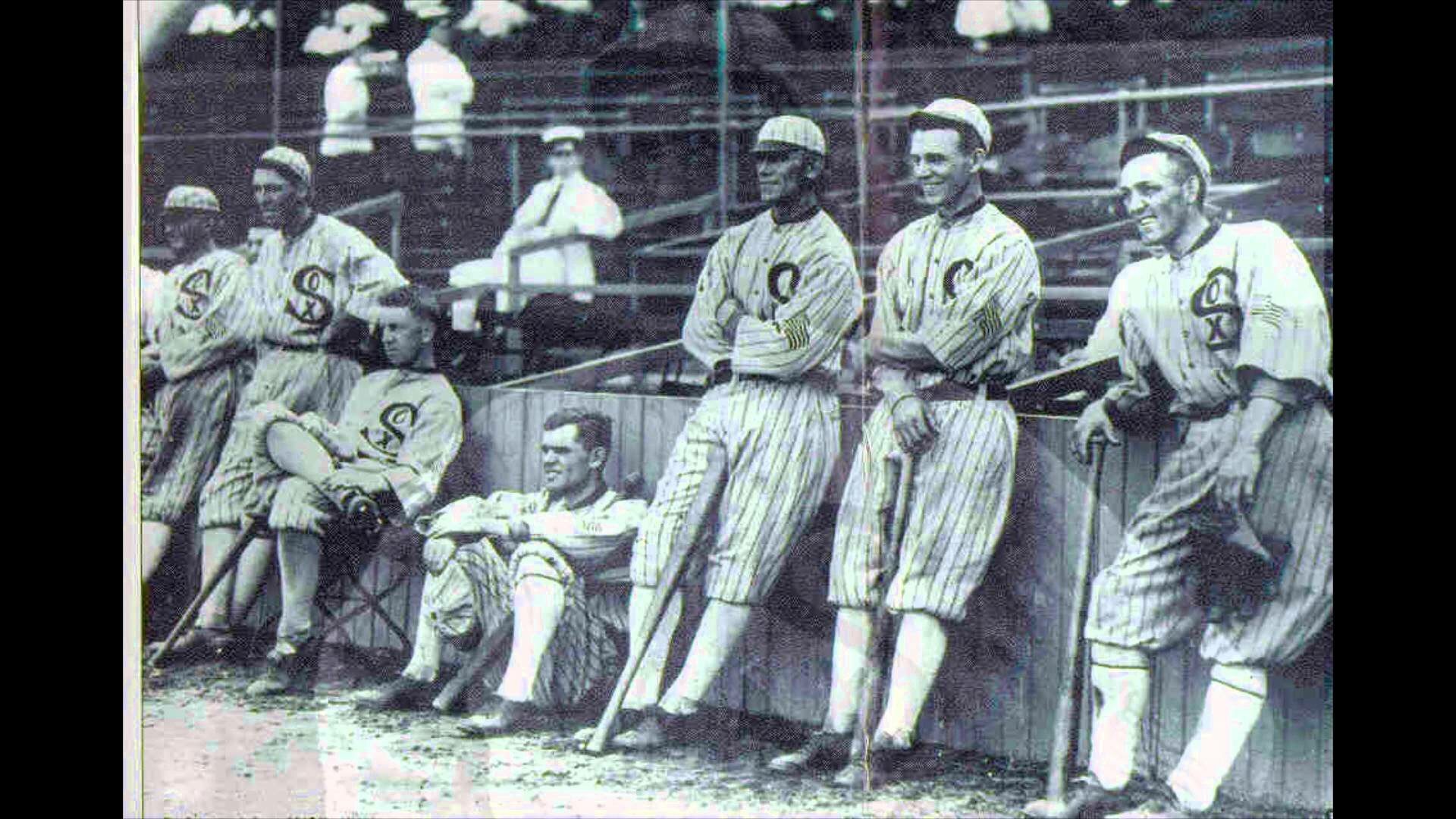

Bill Veeck was a baseball maverick who had an enormous impact on the game. In a career that spanned more than four decades, the chain-smoking red-head had stints owning the Cleveland Indians, St. Louis Browns, and Chicago White Sox [twice]. An open-minded innovator, he helped introduce the designated hitter, interleague play, expansion, and a playoff system to Major League Baseball.

A clever and creative promotor, Veeck brought a midget to home plate and explosives to the outfield at Comiskey Park. He was a charismatic everyman, and the last owner to purchase a franchise that was not filthy rich. Veeck was adored by the press and had a genuine affinity for the folks in the cheap seats. “I have discovered in 20 years of moving around a ballpark that the knowledge of the game is usually in inverse proportion to the price of the seats,” he observed.

Veeck was the first owner to allow fans to buy tickets over the phone and the first to sell season-ticket plans. After becoming minority owner of the Cleveland Indians in 1946, he infused life into the moribund franchise. He put the Indians’ games on radio and hired a clown, Max Patkin, to be a coach. After a fan complained the Indians were honoring everyone but the average Joe, Veeck staged a “Good Old Joe Earley Night.”

Born in Chicago in 1914, William Louis Veeck Jr. was the son of a sportswriter. William Sr. was named president of the Chicago Cubs when young Bill was four. As a teenager, Veeck worked as a vendor, ticket salesman and junior groundskeeper at Wrigley Field. When his father died unexpectedly in 1933, Bill dropped out of college to work for Phillip Wrigley, who had taken over the club the year before. Aiming to beautify Wrigley Field, Veeck designed the iconic hand-operated scoreboard, installed bleachers and planted ivy on the walls of the outfield.

He left Chicago in 1941 and bought a stake in the Triple-A Milwaukee Brewers. He gave away live animals during games and staged weddings at home plate. To accommodate night workers in war factories, Veeck scheduled a game for 8 a.m., serving cereal himself while dressed in pajamas. Five years and three pennants later, he sold the Brewers for a $ 275,000 profit.

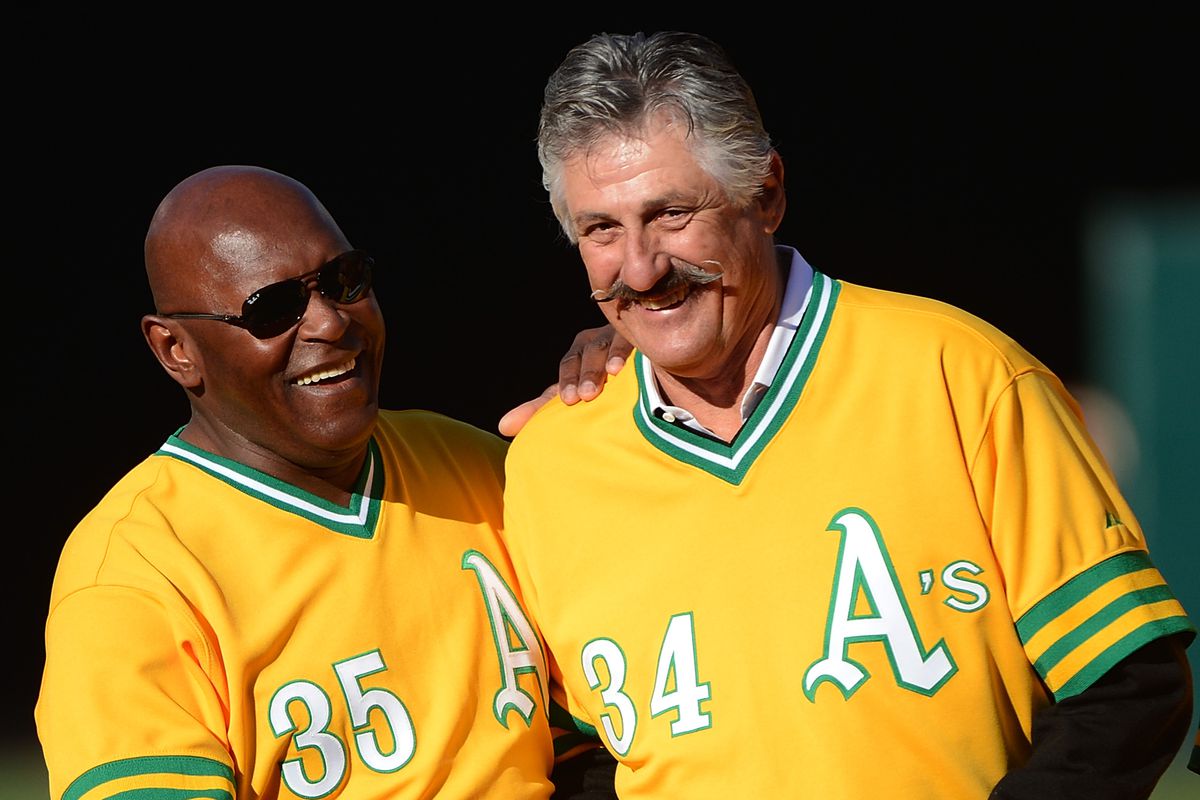

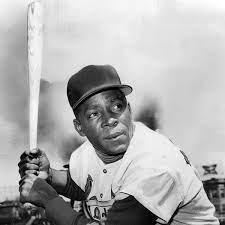

In 1947, Veeck signed Larry Doby as the first African-American in American League history. “One by one, [manager] Lou Boudreau introduced me to each player,” Doby recalled. “All the guys put their hand out – all but three. As soon as he could, Bill Veeck got rid of those three.” The following year, he signed 42-year-old Satchel Paige, making the Negro League legend the oldest rookie in MLB history. Paige helped Cleveland win the 1948 World Series – the last time the Tribe has won the Fall Classic.

After he brought 14 African-American players to Cleveland’s spring training in 1949, The Sporting News dubbed Veeck the “Abe Lincoln of baseball.” He unsuccessfully championed shared radio and television revenue to provide parity between large and small market teams; an idea the NFL embraced a decade later. The idea allowed the NFL to grow into the most profitable sports league in the world.

In 1951, Veeck purchased the struggling St. Louis Browns. Hoping to drive the National League Cardinals out of town, he introduced some of the most famous publicity stunts in baseball history. In August 1951, Veeck sent 3’7” stage performer Eddie Gaedel to pinch hit in the bottom of the first in a game against Detroit. Wearing uniform number “1/8,” Gaedel drew a walk on four pitches and was replaced by a pinch-runner. The next day, AL president Will Harridge denounced the stunt as a mockery of the game and voided Gaedel’s contract.

Five nights later, Veeck held Grandstand Manager’s Day, in which fans were given placards that told Browns’ manager Zack Taylor whether the team should steal a base, bunt or change pitchers. While Taylor puffed a pipe and relaxed in a rocking chair, the crowd skippered the Browns to a 5-3 win over Connie Mack’s Philadelphia Athletics to end a four-game skid. Attendance doubled under Veeck’s leadership, yet the Browns’ financial woes continued. Following the 1952 season, the wildly-popular owner was forced to sell his team to a group from Baltimore, where they became the Orioles.

Nicknamed Sport Shirt for his favorite attire, Veeck bought the Chicago White Sox in 1959 and guided them to their first pennant in 40 years. He installed baseball’s first exploding scoreboard – complete with fireworks, sound effects and ten electric pinwheels that went off after White Sox homers. Veeck was the first to place players’ names on the back of their uniforms, and the club set attendance records in Veeck’s first two seasons on the South Side.

In 1961, poor health forced Veeck to sell his share of the team. But 14 years later, he reappeared and saved the Sox from leaving Chicago. On Opening Day 1976, Veeck – who lost his right leg in World War II — served as the peg-legged fifer for a Bicentennial-inspired Spirit of ’76 parade. He twice reactivated Minnie Minoso, allowing the White Sox great to play in five decades. Veeck hired Harry Caray and encouraged him to sing Take Me Out to the Ball Game, which became a staple in ballparks throughout the league. Not all of Veeck’s ideas were brilliant, however. He had his team take the field in short pants and delivered relief pitchers to the mound in golf carts – a fad that is making a comeback.

Veeck’s biggest fiasco came in June 1979, when a Chicago disc jockey planned to explode disco records on the field between games of a doubleheader. Disco Demolition Night turned into a riot, with thousands of fans storming the field and forcing the umpires to postpone the second game. The next day, the visiting Detroit Tigers got the victory via forfeit.

Bill Veeck sold the White Sox in 1981. Five years later, he died of cancer, at 72. Mr. Veeck was inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1991.

In 2004, Business Week named Bill Veeck one of the great business innovators of the previous 75 years.