Walter Lanier Barber changed the vocabulary of baseball.

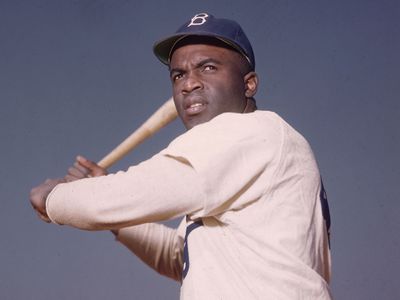

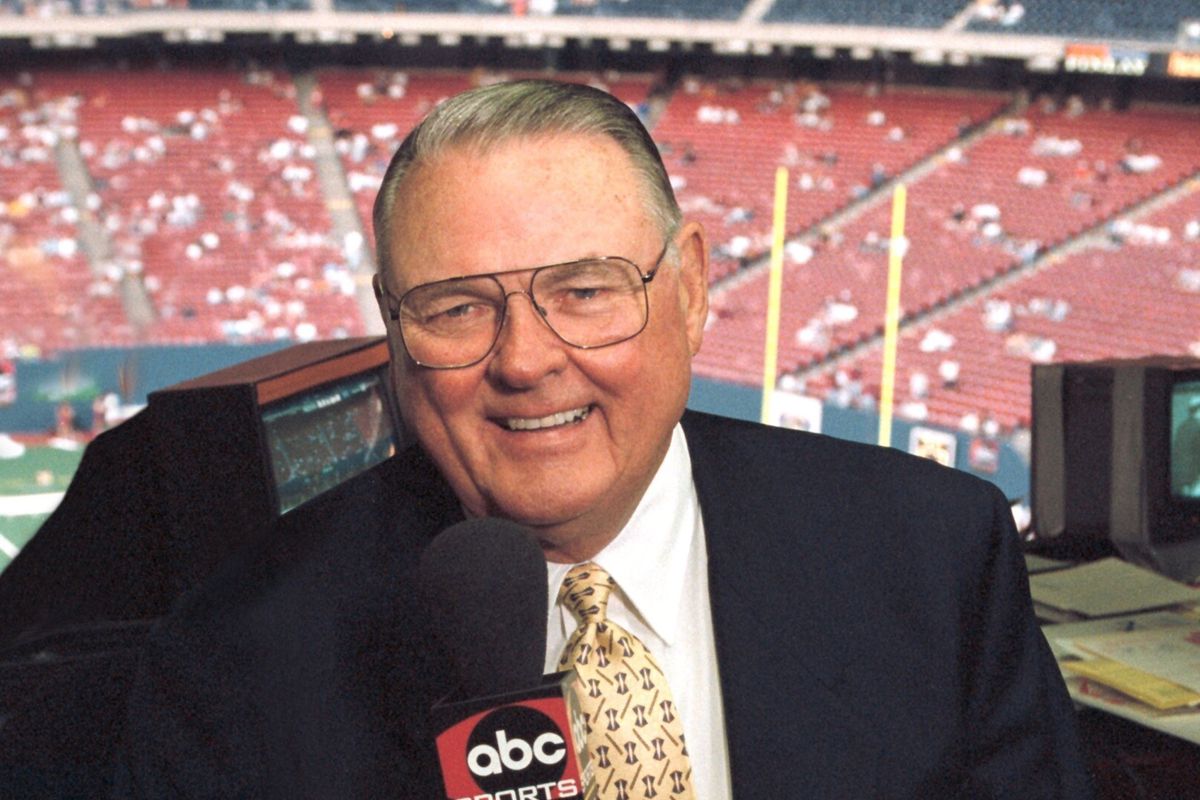

Nicknamed “Red” for the color of his hair, Barber was a pioneering sportscaster for over three decades. From the 1930s through the 1960s, he was primarily known for calling baseball on radio—and nobody did it better than the “Ol’ Redhead.” Widely admired for his folksy style, Barber coupled his barnyard metaphors from the South with scrupulous grammar and superb delivery. He called baseball’s first night game in May 1935 and the sport’s first televised contest in August 1939 at Brooklyn’s Ebbets Field [Daily Dose, 10/30/15]. Barber broadcast Jackie Robinson’s first season with the Dodgers and Roger Maris’s 61st home run [Daily Dose, 9/10/15]. Mr. Barber gave Vin Scully [Daily Dose, 11/27/15] his first broadcast assignment and later hired him to do Dodgers baseball on radio. “He was a profound influence on my life,” said Scully, “and a major reason for any success that I might have had in this business.” In his 33-year career, Barber called 13 World Series, four baseball All-Star games, five Army-Navy games, four NFL championship games, and 11 college bowl games, including the Orange, Sugar and Rose Bowls.

Born in Columbus, Mississippi—home of playwright Tennessee Williams and part of the Mississippi Delta’s Golden Triangle–on this date in 1908, Walter was the oldest of three children. His father was a locomotive engineer and his mother taught English. “My mother gave me an ear for language,” recalled Barber. “My father was a wonderful raconteur, a natural storyteller. He’d sit out on the porch and tell stories by the hour.” Blending these inherited qualities, Barber later wove verbal mosaics which beautifully represented his special gift. At ten, Barber moved with his family to Sanford, Florida. At 21, he hitchhiked 135 miles to Gainesville and enrolled at the University of Florida, where he majored in Education. Barber got a job as a janitor at WRUF, the campus radio station. In January 1930, an agriculture professor had been scheduled to read a paper over the air. When he failed to show, janitor Barber was called in as a substitute. After he read Certain Aspects of Bovine Obstetrics, Barber decided to switch careers. He became WRUF director and chief announcer and, that autumn, covered the Gators football season opener. Barber’s first broadcast was so bad that he was pulled off the air, later calling it, “Undoubtedly the worst broadcast ever perpetrated on an innocent and unsuspecting radio audience.” Other announcers were tried for the next two games. While off, Barber attended Gator practices, picking the brains of the assistant coaches. He learned how to prepare for a broadcast and talked his boss into giving him another chance, launching a legendary broadcasting career. Four years later, he was hired by Larry MacPhail—for 25 dollars a week—as radio voice of the Cincinnati Reds

On Opening Day 1934, 26-year-old Red Barber took his place behind a microphone and broadcast the first major league game he had ever seen. For the next five years, he called games from the stands of Cincinnati’s Crosley Field. When MacPhail moved to become president of the Brooklyn Dodgers in 1939, he took his play-by-play man along. Barber spent 14 seasons in Brooklyn, also covering football for the New York Giants, AAFC Dodgers [Daily Dose, 9/6/16] and Princeton University. in 1940, he called the first nation-wide broadcast of the NFL title game, when the Chicago Bears trounced the Washington Redskins, 73-0. As sports director for the CBS Radio Network, Barber gave Vin Scully his first job, hiring the 21-year-old Fordham grad to cover a Boston University-Maryland football game from the roof of frigid Fenway Park in November 1949. Barber was so impressed with Scully’s work that he offered him a spot in the Dodgers booth the following spring and Scully remained with the Dodgers for 65 years. Prior to the start of the 1954 season, the New York Yankees hired Barber, where he joined the immensely popular “Voice of the Yankees,” and future hall-of-famer, Mel Allen. Their contrasting styles created one of the greatest duos in the history of sports broadcasting. “Barber was white wine, crepes suzette, and bluegrass music,” wrote Curt Smith in Voices of Summer. “Allen was hot dogs, beer, and the U.S. Marine Corps band.”

Baseball and radio go together like peanut butter and jelly. The pace of the game allows the best broadcasters to create word-pictures for listeners, and no broadcaster in history did it better than Red Barber. With a down-home country style and a voice of ginger honey, Barber had a crisp, conversational delivery. Considered the first reporter to broadcast baseball, his preparation was meticulous. Vin Scully called Barber, “The consummate reporter, perhaps the most literate sports announcer I ever met.” He brought a taste of the South to Brooklyn. A team in control was “sitting in the catbird seat,” the diamond was “the pea patch,” a runner who broke up a double play “swung the gate on him,” often resulting in a “rhubarb.” An easily caught fly ball was a “can of corn,” while a ball that was difficult to get a grip on was “slicker than boiled okra.” Barber’s signature catchphrase, “Oh, Doctor!” was later used by Jerry Coleman, a former New York Yankees infielder who became Barber’s partner for Yankee broadcasts. Ever the southern gentleman, Barber identified players as Mister, Big Fella, and Old—as in “Old number 13, Ralph Branca, coming in to pitch.”

Barber kept a three minute egg timer—an hourglass—on his desk in the booth. Every time the sand ran down, he repeated the score and flipped his timer over. This approach became the standard, as generations of announcers–including Scully and the great Curt Gowdy [Daily Dose, 7/31/15]–frequently report the score throughout a broadcast. His integrity and fidelity to getting the [sometimes harsh] facts to the listening audience cost him two jobs. After Walter O’Malley took control of the Dodgers in the early 1950s, he fired Barber for not flavoring his commentary to be more supportive of the team. Barber’s career ended on a sour note in 1966, when the Yankees fired him for comments about low attendance at the ballpark. On a chilly, rainy day in September when baseball’s marquee franchise had fallen to last place, the Yankees played a home game before 413 fans. Barber asked for a television shot of the empty seats in The House That Ruth Built. The director refused and Barber—who was first and foremost a reporter—announced, “I don’t know what the paid attendance is today—but whatever it is, it is the smallest crowd in the history of Yankee Stadium…and this smallest crowd is the story, not the ballgame.” Days later, the Yankees did not renew his contract and, after 33 years, Red Barber retired from broadcasting.

In 1978, Mr. Barber became the first recipient of the Ford C. Frick Award, given annually to a broadcaster for major contributions to baseball. He and Allen were the first broadcasters inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame. The author of six books, Barber is a member of the inaugural class of the American Sportscasters Hall of Fame. Following the end of his broadcasting career, Barber contributed to Ken Burns’ documentary, Baseball. He came out of retirement in 1981 to begin a second career doing Morning Edition for National Public Radio, where every Friday morning he chatted about more than just sports. In 1990, Barber received a Peabody Award for his NPR broadcasts. The Red Barber Radio Scholarship is awarded each year by the University of Florida’s College of Journalism and Communications to a broadcasting student. A WRUF microphone, used by Barber during the 1930s, is on display at the National Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown. Walter Lanier Barber died in Tallahassee in 1992. Three years later, the Ol’ Redhead was posthumously inducted into the National Radio Hall of Fame.