Ben Johnson was at the center of the most infamous sporting moment in Olympic history.

Born to a working-class family in Falmouth, Jamaica, December 30, 1961, Benjamin Sinclair Johnson shares a birthday with Tiger Woods [1975] and LeBron James [1984].

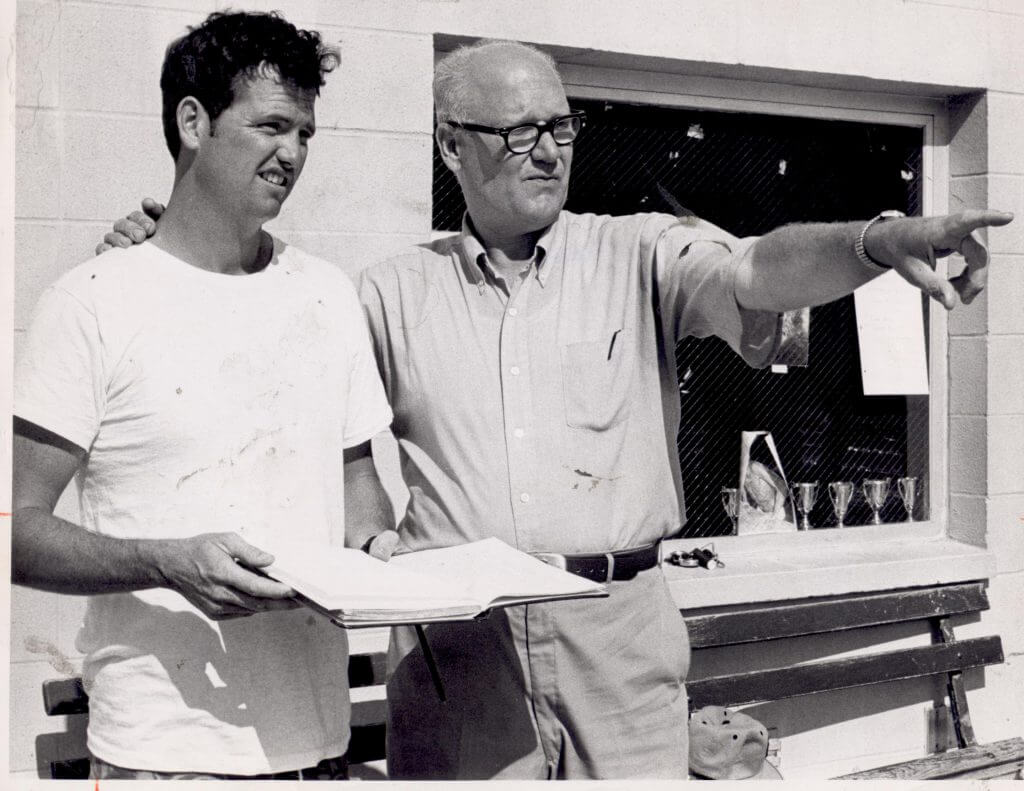

A skinny kid who contracted malaria at three, Johnson moved to Canada with his mother and older brother at 15. He found solace on the track and soon found his calling in sprinting. In 1976, Johnson met Charlie Francis, a former Canadian Olympic sprinter, and coach of the Scarborough Optimists track club. He began training under Francis at York University where his life would change forever.

Francis took Ben Johnson under his wing and started the young sprinter on a course of steroids beginning in 1981, believing it was the only way to compete in a sport rampant with performance-enhancing drug use.

Johnson quickly transformed from scrawny to muscle-bound. His first international success came at the 1982 Commonwealth Games, where he won silver medals in the 100m and 4 x 100m relay events. At the 1984 Los Angeles Olympics, Johnson finished third in the 100m, behind Americans Carl Lewis and Sam Graddy, and claimed bronze in the 4 x 100m. By the end of 1984, he was Canada’s top sprinter after lowering the national 100m record to 10.12.

Ben Johnson’s PED use escalated. In 1985, the 5’10”, 165-pounder moved from injecting stout doses of HGH to the steroid Dianabol — used for lean muscle mass, increased stamina and strength.

He beat Lewis, the reigning World and Olympic champion, for the first time in Zurich later that year and rumors immediately began circulating. It was rare for an athlete to make the improvements Johnson had made, especially in such a short period of time.

Prior to the 1985 meet in Zurich, Lewis had beaten Johnson in all six of their career races.

In the next three years, the rivals met seven times, with Johnson winning five. At a 1987 race in Seville, Spain, Johnson received a higher appearance fee than Lewis for the first time. The media fueled the rivalry, portraying Johnson as an overpowering, uneducated brute. The American was made out to be the guy in the white hat, with a graceful running form.

When Ben Johnson and Carl Lewis met in the men’s 100m final at the Seoul Olympics in September 1988, it was the most hyped race in the history of the Games.

Already each other’s fiercest rival, Lewis was the defending Olympic champion, having won four years earlier at his coming-out party in Los Angeles. But Johnson had dominated him since 1985 and was the current holder of the world record [9.83], which he’d set at the 1987 World Championships.

More than 100,000 people crammed into Seoul’s Olympic Stadium to watch the showdown, billed as The Race to End All Races.

“When the gun go off, the race be over,” Johnson had predicted – and he wasn’t wrong. Although his start was only slightly quicker than his rival’s, Johnson left Lewis and the rest of the field – which included former world record holder Calvin Smith and future gold medalist Linford Christie — in his wake. In a race that not only lived up to the hype but exceeded it, the Canadian smashed the world record in a display of power never before seen in track and field. Against the greatest array of sprinters ever assembled – four in the field broke the ten-second barrier – Johnson bettered his own world mark by a whopping four-tenths of a second.

At the finish, the beaming Johnson shot his right arm into the air in celebration, then took a victory lap. Canada was overjoyed about its new hero, who became the country’s first sprinter to win the Olympic 100m final since Percy Williams in 1928. Canadian Prime Minister telephoned Johnson on live TV to thank him for “a marvelous evening for Canada.”

Following the medal ceremony, the triumphant sprinter eulogized in the press room. “I’d like to say my name is Benjamin Sinclair Johnson Jr., and this world record will last 50 years, maybe 100. A gold medal – that’s something no one can take away from you.”

But they could. And they did.

Two days later came the news that stopped the Olympics dead. Johnson had tested positive for the banned anabolic steroid Stanozolol.

The International Olympic Committee stripped him of his gold medal and world record, awarding the gold to Lewis and silver to Britain’s Christie. From hero to zero, the disgraced Johnson left for Seoul as a Canadian and returned Jamaican-born. Within days, Mulroney was back on television talking of “a moment of great sorrow for all Canadians.” Upon arriving at the Toronto airport, Johnson was booed.

Johnson attempted a comeback, but it was stillborn after he again failed a drug test in 1993 and was banned for life. Although he later admitted to taking steroids for eight years, Johnson insists that he was innocent of taking banned substances at the 1988 Olympics, and that he was sabotaged by someone spiking his drink at the anti-doping center in Seoul after the race.

The greatest rivalry North America has seen in the last two generations played out over ten seconds in 1988. The 100m Olympic final in Seoul has been called the dirtiest race in history, as six of the eight finalists that lined up that September day would fail drug tests or be implicated in their use during their careers, including Lewis and Christie. But Ben Johnson was the most vilified.

“There were many dark days,” he later said. “The whole world painted me as a loser and a cheater, but I wasn’t alone when it came to the cheating. There were others. People know this now, but back then the media made it look like I was the only one. It was hard.”

On the 25th anniversary of the race, a Canadian Broadcasting Company Radio documentary revealed that 20 athletes tested positive for drugs but were cleared by the IOC at the 1988 Seoul Olympics. In 2013, an IOC official told the CBC that endocrine profiles done at the Seoul Games indicated that 80 percent of the track and field athletes tested showed evidence of long-term steroid use. Only Johnson had his medal stripped.