In the long history of boxing, perhaps even in the entire history of sports, no champion has ever been more hated than Sonny Liston.

Liston was despised by the rich and disliked by the poor. He was detested by whites and blacks, loathed by the press, and even the President of the United States held animosity toward him. Liston fought professionally for 17 years, going 50-4 [39 by KO] between 1953 and 1970. One of the most dominant fighters of his era, he was the original Mike Tyson – The Baddest Man on the Planet.

An unreformed ex-con who once worked as “mob muscle,” Sonny Liston could barely read and spoke like a thug. His run-ins with the police were legendary. Liston was kicked out of St. Louis, Philadelphia and Denver – all because of his beef with cops. Portrayed as mean and surly, the press disparaged his menacing demeanor and criminal background. Liston was viewed to have organized crime in his corner, and soon became the fighter America loved to hate. In December 1963, he appeared on the cover of Esquire magazine as a black Santa Claus – the last man on earth America wanted to see coming down its chimney. It cost the magazine $ 750,000 in ad sales and provoked piles of angry letters.

A devastating puncher, Liston achieved most of his wins by knockout. Standing 6’1’ and weighing 213, he had a powerful physique and a disproportionate reach of more than 80 inches. The Bear’s fists measured 14 inches around, the largest of any heavyweight champion. Boxing writer Mort Shank said his hands “looked like cannonballs when he made them into fists.”

Charles L. Liston was the son of a sharecropper. His abusive, alcoholic father had 25 children – 13 with his first wife and a dozen with his second. Sonny was the 24th of those 25 kids. Born in St. Francis County, Arkansas, his listed date of birth is May 8, 1932. No official record exists because Arkansas did not make birth certificates mandatory until 1965. Liston grew up working in the cotton fields and never learned to read. He left home as a teen, landing in St. Louis.

Liston, who had grown to 6’, 200 pounds by 16, soon found trouble with the law. He was arrested more than 20 times. In 1950, he was convicted on two counts each of larceny and first-degree robbery and was sentenced to five years in the Missouri State Penitentiary in Jefferson City. Liston was introduced to boxing while in prison. He was paroled in 1952, and quickly captured the Chicago Golden Gloves championship, beating 1952 Olympic heavyweight champion Ed Sanders for the title. In his early 20s, Liston also won the prestigious Intercity Golden Gloves title and advanced to the quarterfinals of the 1953 National AAU Tournament.

Liston made his professional debut in St. Louis in September 1953, knocking out Don Smith in the first round. Rumors began circulating that Liston had ties to the mob, as his financial backers were close to underworld figures, and the ex-con supplemented his income by working for racketeers as an intimidator-enforcer. Liston’s first loss came in his eighth pro fight, when he lost a split decision to Marty Marshall. By May 1956, he had run his record to 14-1 when he was arrested for assaulting a policeman and stealing the officer’s gun. Liston was sent away for nine months. No longer welcome in St. Louis, he moved to Philadelphia and returned to boxing.

Following his loss to Marshall, Liston won his next 26 fights. Combining an intimidating ring presence with awesome power and a perpetual scowl, he became the top heavyweight challenger. The world heavyweight champ was Floyd Patterson, whose handlers refused to give Liston a title shot due to his links to organized crime. The NAACP feared a Liston victory over Patterson would hurt the civil rights movement. During a visit to the White House in January 1962, President John F. Kennedy urged Patterson to avoid Liston, citing concerns over his ties to the underworld.

Patterson finally agreed to meet Liston for the world title in September 1962, in Comiskey Park in Chicago. It was the third title defense of his second reign as world heavyweight champion. Despite his 38-2 record, Patterson entered the bout as an 8-5 underdog. More than 600,000 boxing fans watched the fight on closed circuit television in 260 locations throughout the U.S. and Canada, and 18,894 more filed into Comiskey to witness the bout in person. What they got was a mismatch. Liston, with a 25-pound weight advantage, knocked Patterson out at 2:06 of the first round. It was the first time in history that a heavyweight champion had been knocked out in the opening round.

With a rematch clause in their contract, Patterson and Liston met again in Las Vegas in July 1963. In his first title defense, The Bear stalked Patterson, knocking the former champ down three times. Patterson was counted out 2:10 into the first round. He would go on to fight for the title in vain three more times in his career before retiring in 1972.

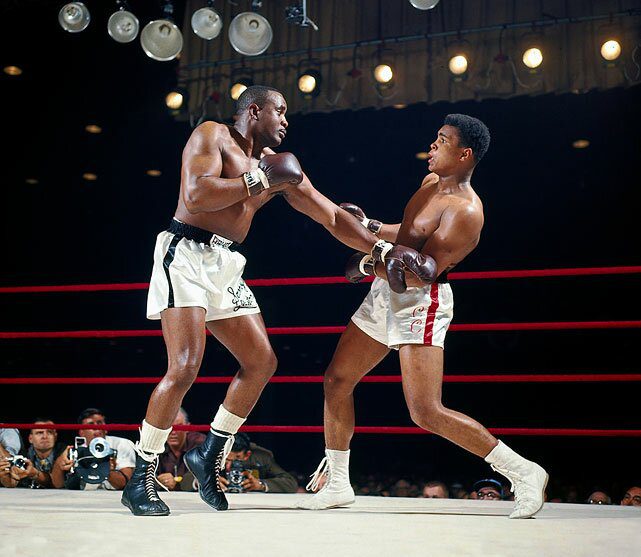

Liston made his second title defense against Cassius Clay in Miami February 25, 1964. Considered invincible, Liston was installed as a 7-1 favorite, but his 17-month reign as champion ended in south Florida. Using superior speed and footwork, the 22-year-old Clay out-boxed the slower champion, who was ten years his senior. When Liston was unable to answer the bell for the seventh round, Ali was declared the winner – and new champion – by technical knockout. It was the first time since 1919 that a world heavyweight champion had quit on his stool.

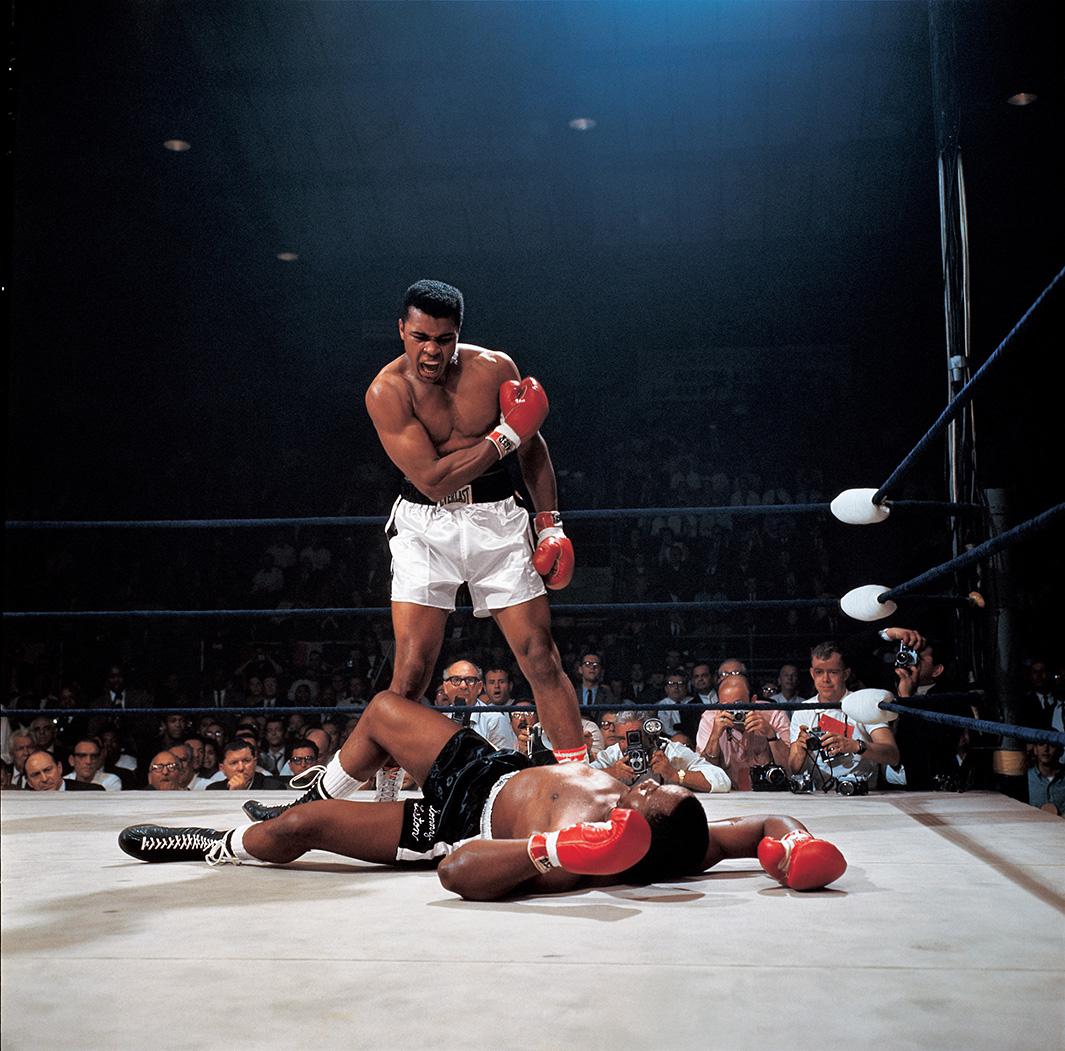

The two heavyweights met in Lewiston, Maine, 15 months later in what became one of the most controversial matches in the history of the fight game. Midway through the first round, Liston threw a left jab and Ali [Clay changed his name to Muhammed Ali after their first fight] went over it with a fast right. Though it appeared that Ali’s fist had barely grazed Liston, the former champion dropped to the canvas. From his back, Liston rolled over, got to his right knee and then fell on his back again. Many in attendance did not see Ali deliver what came to be known as the Phantom Punch, and chaos ensued. Referee Joe Walcott counted Liston out at 2:12 of the first round. Many of the 2,434 fans in attendance at the Central Maine Youth Center yelled “Fix!” To this day, many believe Liston threw the fight.

Labeled a “bad negro,” Liston became a diminished figure after the Ali fights. He moved to Las Vegas, where he launched a comeback in 1966 and won 14 consecutive fights, a dozen by knockout. After losing a brutal bout to Leotis Martin in 1969, he climbed into the ring in June 1970 one final time, stopping Chuck Wepner in the ninth round. To supplement his paltry income, the former champion peddled drugs out of his pink Cadillac.

On January 5, 1971, Geraldine Liston found her husband’s lifeless body in their Las Vegas home upon returning from a two-week trip. The cause of death was listed as lung congestion and heart failure, although Liston had fresh needle marks on his arms and police discovered heroin and a syringe in the house. Following an investigation, Las Vegas police concluded there were no signs of foul play and declared Liston had died of a heroin overdose on December 30, six days before his body was discovered.

Charles “Sonny” Liston is buried in Las Vegas beneath a gravestone that simply reads, “A Man.” Boxing writer Herb Goldman lists Liston as the second-greatest heavyweight in history, behind Ali. The Ring magazine lists him as the seventh-greatest heavyweight of all time.

On this date in 1962, Sonny Liston knocked out Floyd Patterson in the first round at Comiskey Park in Chicago to become heavyweight champion of the world.