Sidd Finch turns 34 today.

On this date in 1985, Sports Illustrated magazine published a story entitled “The Curious Case of Sidd Finch.” Conceived and written by long-time contributor George Plimpton, it is one of the magazine’s most talked-about stories. And it’s the greatest April Fool’s Day prank of all time.

In early January 1985, Sports Illustrated managing editor Mark Mulvoy realized that April 1 was falling on a Monday, the cover day of the then-weekly magazine. “Right away, I thought, we gotta do an April Fools’ story,” recalled Mulvoy. He and outside text editor Myra Gelband kept the idea secret and assigned senior writer George Plimpton to write a feature on April Fools’ sports stories. Plimpton, who died in 2003, was the finest participatory journalist ever to type a word. He wrote first-person pieces about playing quarterback for the Detroit Lions [Paper Lion], boxing with Archie Moore and playing goalie for the Boston Bruins.

When Plimpton couldn’t come up with enough material on April Fools’ sports stories, he invented one. The fertile-minded Plimpton told the tale of Hayden Siddhartha “Sidd” Finch, a 28-year-old rookie pitcher for the New York Mets. Born in New York and raised in an English orphanage, Finch was adopted by an archaeologist who later died in a plane crash in Nepal. After briefly attending Harvard, he went to Tibet to learn siddhi, the yogic mastery of mind-body under the great poet-saint Lama Milaraspa, where he learned the art of the pitch.

Sports Illustrated is not going to devote 14 pages to a story about a baseball player who doesn’t exist.

Sidd Finch could throw a fastball an amazing 168 miles per hour — far above the “mere” 103 recorded by Nolan Ryan — with pinpoint accuracy and without needing to warm up. He pitched wearing only one shoe – a heavy hiker’s boot on his right foot. The Mets scouting report gave the mysterious prospect a “9” on the velocity and control of his fastball when “8” was the highest score on the scale. Finch, a devout Buddhist who played the French horn as well as he threw a baseball, had to decide between a career in the big leagues or in music.

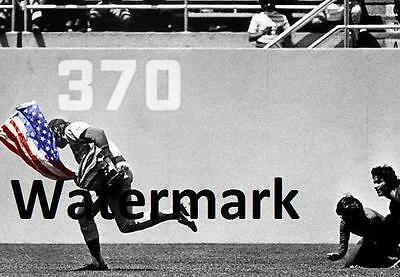

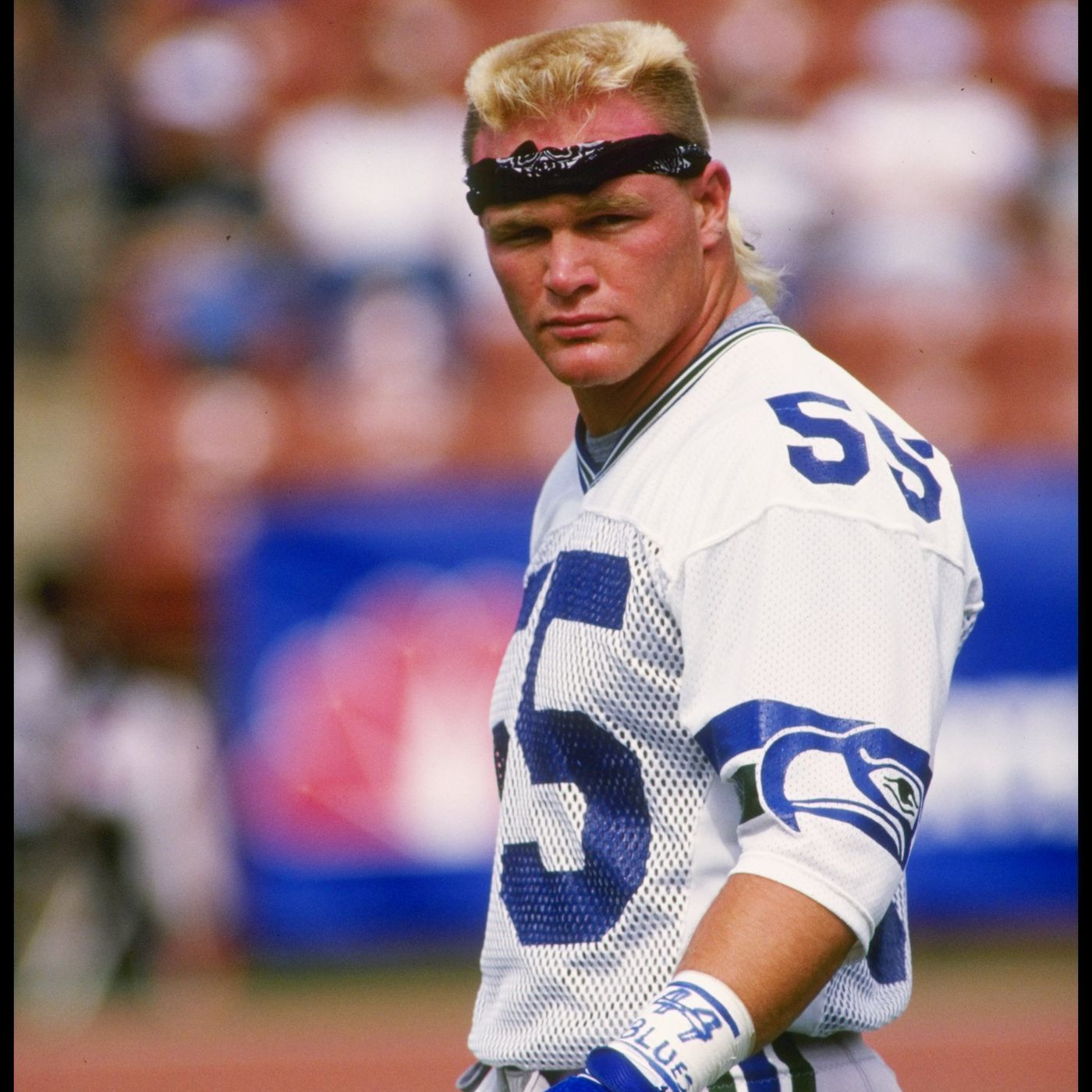

George Plimpton agonized over whether the piece would be good enough, knowing “nothing falls quite as flat as a bad joke.” In order to make the hoax more believable, Mulvoy wanted images to accompany the story. He called upon SI photographer Lane Stewart to handle the job. Stewart recruited his friend, Joe Berton, a 32-year-old middle school art teacher from suburban Chicago, to portray Finch. The 6’4” Berton, who wears a size-14 shoe, averted his face from the camera, adding to the mystique of the story.

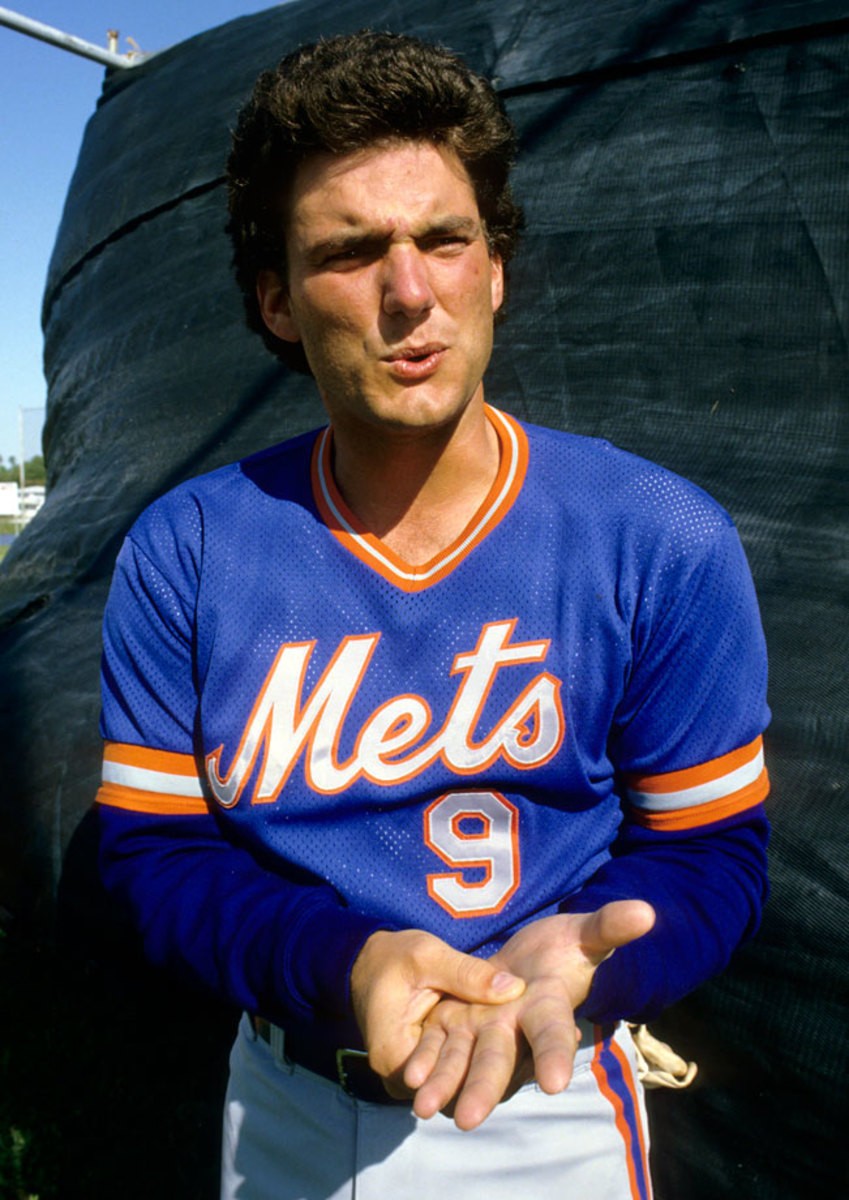

Mets management played along, providing access to players, coaches and a uniform [number 21] for Finch. The team gave Finch a locker between George Foster and Darryl Strawberry. The Mets had their groundskeeper build a secret, canvas-covered batting cage for Finch at the team’s spring training complex in St. Petersburg. Only a handful of Mets players were in on the joke. Most believed Sidd Finch actually existed.

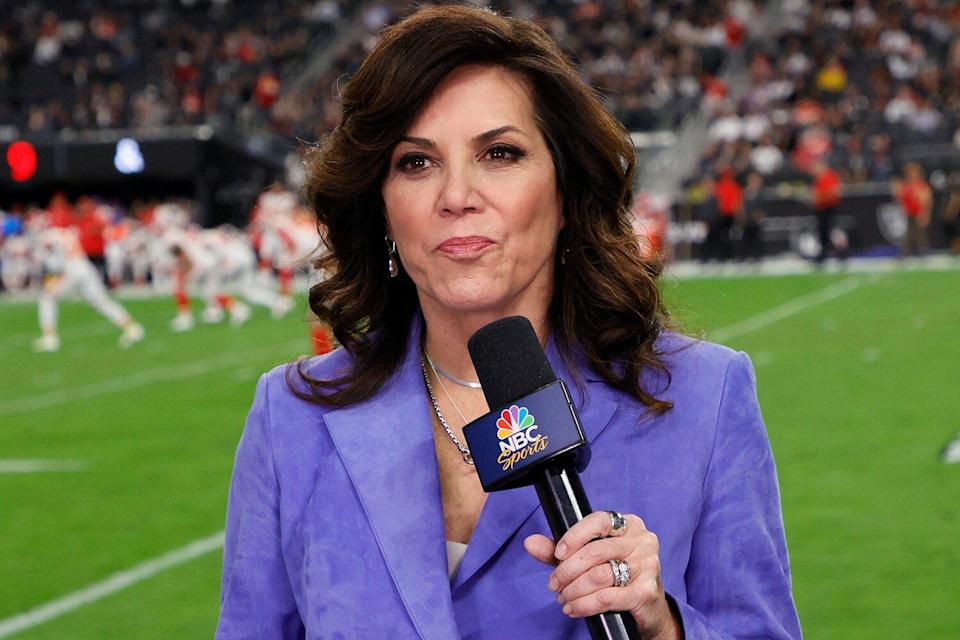

The April 1 issue of Sports Illustrated reached subscribers and newsstands in the final days of March. Originally scheduled for five pages, SI expanded the the feature to 14 pages. Mulvoy’s instincts were right: the images brought credibility to the incredulous story. There’s Sidd, wearing one shoe, throwing at some soda bottles on the beach. There’s Sidd, talking to Mets pitching coach Mel Stottlemyre. The story even included a scouting report by the man who discovered Finch, beaming he “could be the phenom of all time.” The bible of sports journalism – and one of the most respected writers of all time – had uncovered a story that would change baseball, as we know it, forever.

SI publisher Robert Miller – who was kept in the dark about the hoax – was not happy with Mulvoy, fearing the story would compromise the integrity of the magazine.

Millions believed the story and suddenly all of America was talking about this gangly, fire-balling recluse. Two MLB general managers called baseball commissioner Peter Ueberroth at home to ask how their batters could face Finch safely. The St. Petersburg Times sent a reporter to Mets camp to find the phenom. ABC, CBS and NBC sent journalists to Florida for a press conference about Finch. It was even on Nightline with Ted Koppel.

New York newspaper editors were furious that their beat writers had missed the biggest story of spring training. The magazine was flooded with requests for more information on Finch. Soon the Mets were holding “Sidd Finch Day” and fans were asking for Berton’s autograph.

Mets fans celebrated. Strawberry and Doc Gooden had been named NL Rookies of the Year the previous two seasons. “I never dreamed a baseball could be thrown that fast,” said outfielder John Christensen, one of the Mets players who was in on the joke and had allegedly faced Finch in the secret batting cage. “As for hitting the thing, frankly, I just don’t think it’s humanly possible.” Mets fans were overjoyed at their luck of finding such a player.

The furor over the Met from Tibet lasted until April 2, when the Mets called a press conference in St. Petersburg. Berton, dressed as Finch in his Mets uniform, announced he had lost his accuracy and was retiring from baseball. SI received thousands of letters and more than a few angry cancellations. Mets fans became furious that Sidd Finch did not exist. “The messiah had come,” wrote one. “Never had I wanted to believe a story more. I’m crushed.” The buzz exceeded everyone’s expectations at SI, especially Mulvoy’s. Joe Berton, who called the ensuing months the Summer of Sidd, became a celebrity.

Sports Illustrated printed a much smaller article in the following week’s issue reporting Finch’s retirement. On April 15, it was announced the entire thing was a hoax.

The photo of Finch riding a camel was taken two years earlier, when Stewart and Berton were on vacation in Egypt over Christmas.

Plimpton tried to “leave little bread crumb clues” that the story was a hoax within the article itself [the non-obscure hint being that the story was absurd]. The sub-heading of the article read: “He’s a pitcher, part yogi and part recluse. Impressively liberated from our opulent life-style, Sidd’s deciding about yoga – and his future in baseball.” The first letter of these words, taken together, spells “H-a-p-p-y A-p-r-i-l F-o-o-l-s D-a-y. [ah fib]”

“I’ve never had so much fun in my life writing a story,” Plimpton later said. He intended to make the speed of Finch’s fastball 138 miles per hour. It mistakenly came out “168” and Mulvoy insisted he keep it. While formulating his concept for what became the most notorious April Fools’ day hoax in the history of journalism, George Plimpton discovered that the seventh definition of “finch” in his Oxford dictionary was “small lie.”

The popularity of the joke prompted Plimpton to write an entire book on Finch, published in 1987. In April 2015, ESPN released Unhittable: Sidd Finch and the Tibetan Fastball, a 30-for-30 Short about the Sidd Finch phenomenon, as an April Fools’ joke for a new generation. On August 26, 2015, the Brooklyn Cyclones, the Mets’ Single-A affiliate, held a Sidd Finch Bobblehead Night to commemorate the 30thanniversary of the event. The late George Plimpton’s son, Taylor, threw out the first pitch and Joe Berton signed autographs. The bobblehead showed Finch in a Cyclones uniform, with French horn and one bare foot.