The story of Lyman Bostock is not how he died, but how he lived.

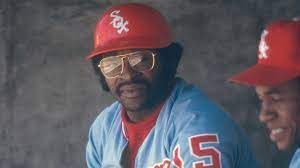

A talented outfielder who played four major league seasons between 1975 and 1978, Bostock was the consummate five-tool player. He played in 526 games in his short career, batting .311 while collecting 624 hits with 23 home runs and 250 RBI. In his first full season in the big leagues, Bostock hit for the cycle against the Chicago White Sox and ultimately batted .323 to finish fourth behind George Brett, Hal McRae and Rod Carew for the 1976 AL batting title.

Only Dave Parker and Carew had higher accrued batting averages than Lyman Bostock from 1976 to 1978. At 6’1”, 180, he could do it all. Bostock had double-digit steal totals in each of his three full seasons. His glove is where fly balls went to die. In the first game of a doubleheader against the Red Sox May 25, 1977, the fleet center fielder tied the major league record by recording a dozen outfield put outs. He tallied five more in the nightcap, establishing a new AL record for put outs in a doubleheader, with 17.

Former Baltimore Orioles manager Earl Weaver once predicted Bostock “will win five or six batting titles before his career is over.”

Born in Birmingham, Alabama, November 22, 1950, Lyman Wesley Bostock was the son of Annie Pearl and Lyman Sr. His father – with whom Lyman was estranged — had been a star first baseman in the Negro Leagues for 15 years and mentored Willie Mays with the Birmingham Black Barons. Bostock’s parents split when he was two, and Annie Pearl and her son relocated to Gary, Indiana, in 1954. Once a vibrant steel city, post-war Gary was a decaying town that offered little opportunity, so the two headed west by bus – Annie Pearl with $7 in her pocket — to Los Angeles, in 1958.

Annie Pearl bought her only child his first glove at eight. It was stolen the next day, and she didn’t have enough money to buy a replacement. A friend at work donated an old left-handed mitt, which the right-handed youngster was forced to use. The only way he could catch the ball was by employing a Willie Mays-style “basket catch,” which Bostock used throughout his career.

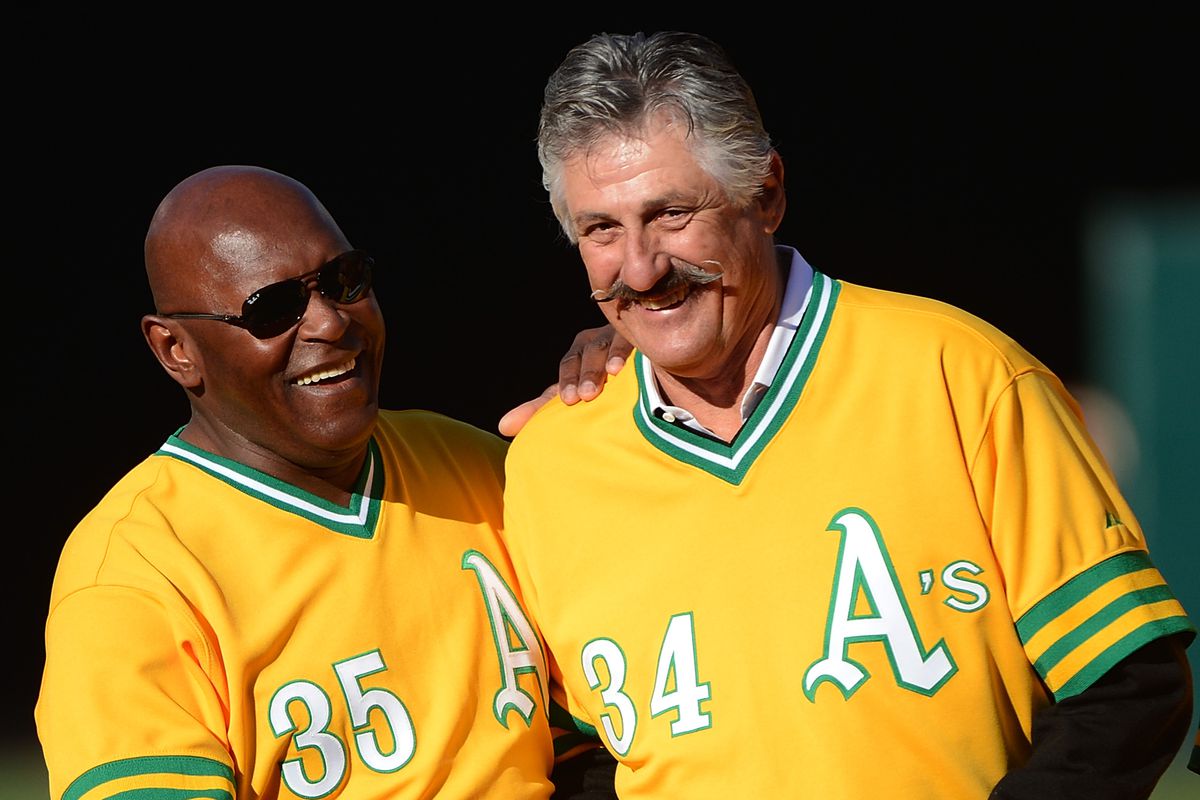

Bostock played baseball at Manual Arts High School, then attended San Fernando Valley State College [now Cal State-Northridge], where he met his future wife, Youvene Brooks. A two-time all-conference player, he led the Matadors to a second-place finish at the 1972 Division II College World Series. Bostock was selected by the Minnesota Twins in the 26th round [596th overall] of the 1972 amateur draft.

After ascending through the Twins’ farm system, Bostock made his big-league debut in 1975, appearing in 98 games and hitting .282. Over the next three seasons, he emerged as one of baseball’s elite hitters. The left-handed hitting Bostock became Minnesota’s everyday center fielder in 1976, batting .323 with 21 doubles and 60 RBI. The 25-year-old exploded the following season, hitting .336 while collecting 199 hits and driving in 90 runs. Following the 1977 season, Lyman Bostock was Major League Baseball’s most sought-after free agent.

The free agency system, which was still new to baseball in the mid-to-late 1970s, was turning players into millionaires overnight. After earning $20,000 with the Twins in 1977, Lyman Bostock signed a five-year, $2.3 million contract with the California Angels for the 1978 season, an astounding figure at the time. Humble and true to his roots, he helped fund the rebuilding of his family’s former church in Birmingham and purchased sporting equipment for underprivileged youth in L.A.

The 1978 campaign started poorly for Bostock. After batting .147 in April, he was so distraught he attempted to pay back his entire month’s salary, saying he had not earned it. The team refused, so Bostock announced his would donate his April salary — $36,000 — to charity. “He came into my office and told me he was reluctant to take his salary,” recalled Angels general manager Buzzy Bavasi. “He said, ‘I’m not doing my job.’ I told him, ‘I won’t let you do that.” When Bostock asked why, Bavasi retorted, “What if you hit .600 next month? You’re sure as hell not getting any more money out of me.”

Bostock’s loyalty was moving. The New York Times wrote: Lyman Bostock is hitting 1.000 in integrity. His batting average, though, is .147.

By late September, Bostock was the Angels’ leading hitter. With a week remaining in the 1978 season, he went 2-for-4 in a game against the Chicago White Sox to raise his average to .296. Following the game at Comiskey Park, as he regularly did when in Chicago, Bostock visited his uncle, Thomas Turner, in nearby Gary, his former hometown. Turner hosted a dinner party for the outfielder and a handful of relatives at his home. Afterward, Bostock and his uncle went across town to visit Joan Hawkins, a woman Lyman had tutored as a teenager but had not seen in nine years.

Turner waited in his gray Buick Electra 225 while Bostock visited briefly with Hawkins in her living room. When Joan asked if she and her sister, Barbara, could catch a ride to a nearby relative’s house, the men agreed to drive them. Little did they know the trouble that awaited them on the street outside.

Leonard Smith married Barbara in 1974. A Gary native, he had a history of violence and a long arrest record. Leonard and Barbara Smith had a volatile relationship, having separated a dozen times during their four years together. One month earlier, Leonard had beaten Barbara after accusing her of coming home too late. She immediately grabbed her children, packed a bag, and moved across town to live with Hawkins. Shortly thereafter, she filed for divorce.

Dubbed Jibber-Jabber for his infectious enthusiasm, Lyman was, according to Angels teammate Rick Miller, “one of the best people you’d ever be blessed to know.”

Hoping to win his estranged wife back, Smith pulled up to Hawkins house on September 23, 1978, at about 10:30 p.m. While sitting in his car, the 31-year-old unemployed steelworker spotted Barbara climbing into the back seat of Turner’s Buick with Bostock – a man Leonard didn’t recognize, but one he was certain was having an affair with his spouse. The fact is, the two had met only hours earlier.

With Turner driving, Hawkins got into the passenger’s seat. Bostock climbed in the back behind her and Barbara Smith sat next to him, on the driver’s side. As the group rode down Fifth Avenue, talking, Leonard Smith followed closely behind. At the intersection of Fifth and Jackson, a budding major league star was caught in the wrong place at the wrong time.

Turner’s car was stopped at a red light. At 10:44 p.m., Smith pulled his vehicle next to the passenger side of Turner’s Buick, rolled down his window, leaned out and fired a shot in the direction of his wife. The single shotgun blast struck Bostock squarely in the right temple. He was rushed to St. Mary’s Hospital in Gary, where he was pronounced dead two hours later. Barbara Smith was hospitalized in fair condition with pellet wounds to her face and later discharged.

Leonard Smith faced 30-60 years in prison if convicted of murdering Lyman Bostock. At his trial in November 1979, Smith’s attorney painted a picture of his client being driven mad by his estranged wife’s philandering ways. The defendant was found not guilty by reason of insanity and ordered to undergo psychiatric treatment in the Indiana state mental hospital in Logansport. Seven months later, psychiatrists declared Smith no longer mentally ill and he was released and allowed to return home. The outpouring of anger over Smith’s freedom convinced Indiana to change its laws to allow those found mentally impaired also be found guilty and imprisoned.

The memory of Lyman Bostock faded quickly. Five days after the outfielder was killed, Pope John Paul died of a heart attack following a mere 33 days as pontiff. Less than a year later, New York Yankees catcher Thurman Munson died in a plane crash.

Leonard Smith died of natural causes in 2010.

Had he lived, Lyman Bostock would have celebrated his 69th birthday this past Friday.