On August 11, 2008, Jason Lezak swam the greatest anchor leg in Olympic history.

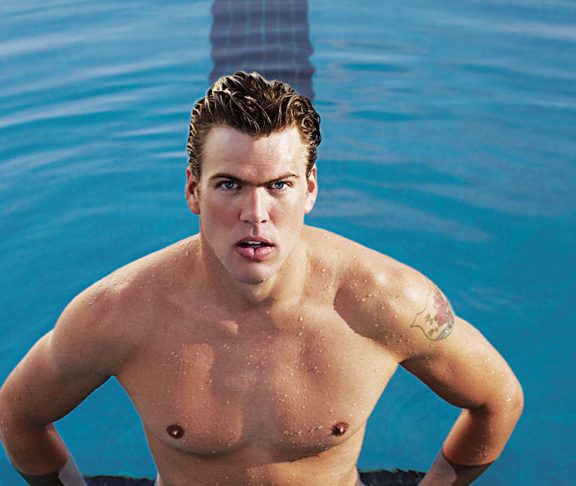

A two-time USA Olympic team captain, Lezak is one of the most accomplished relay swimmers of all time. He competed at the international level from 2000 to 2012, earning spots on four U.S. Olympic teams and capturing eight medals – four of them gold. A 50 and 100-meter freestyle specialist, the 6’4” Lezak is the former American record holder in the 100 free and owns long course records in the 400 freestyle and medley relays.

Gary Hall Jr. dubbed Lezak a “professional relay swimmer” at the 2004 Olympic Trials. The consummate team guy, Lezak is one of few elite swimmers not to have a personal coach. He owns 34 international medals, including 23 golds, and captured five world championships in short course freestyle.

Jason Edward Lezak was born in Bellflower, California, November 12, 1975, to a mom who taught elementary school science and father who sold leather goods. He grew up in nearby Irvine and attended Irvine High, a Blue Ribbon School with a strong swimming pedigree. Alma mater of seven-time Olympic medalist and two-time American Swimmer of the Year Amanda Beard, Irvine High School hosted the 2010 Pan Pacific Swimming Championships.

Lezak skipped the 2009 World Championships to compete in the Maccabiah Games in Israel, where he was selected to light the flame during the opening ceremony. While there, he won four gold medals and was inducted into the International Jewish Sports Hall of Fame.

A 1994 high school All-American in both swimming and water polo, Lezak attended the University of California Santa Barbara. His best collegiate performances came as a junior, when he finished fifth and sixth at the NCAAs in the 50 and 100 freestyle, respectively. In the summer of 1998, Lezak won the 100 free at the U.S. nationals. Two years later, at the 2000 Sydney Games, he won his first Olympic gold medal as part of the USA’s 400 medley team and became the top-ranked sprinter in the world.

Lezak took part in two of the most painful races in American 4×100 freestyle history. At the 2000 Games in Sydney, the U.S. men failed to win Olympic gold for the first time since the event was introduced in 1964. The Australians dethroned the U.S., then mockingly strummed air guitars in front of their faces on the swim deck following the race. Lezak took it personally. “The United States owned that event for more than 30 years, and to lose it was tough for all of us,” he said. Four years later in Athens, the U.S. men fell to the bronze medal.

Lezak was part of both of those underwhelming U.S. quartets. He had also experienced individual disappointment on the international stage. In 2004, Lezak arrived in Athens as the world record holder and ranked number one in the world in the 100 free. But he made a huge tactical mistake in Greece, taking it too easy in the preliminaries to save his energy and failing to advance.

Most of the talk coming into the 2008 Beijing Games centered around Michael Phelps, the most decorated swimmer in history who was seeking to break Mark Spitz’s record seven gold medals at a single Olympics. The Baltimore Bullet was heavily favored in six of his races, but the 4×100 [along with the 100m butterfly] was one of his two major tests. Moments before the start of the race, Lezak gathered his teammates in a quiet hallway. “I reminded them that we lost this race the last two Olympics,” said the captain. “We’re supposed to win this. This is USA’s race. This is a 400, not a 4×100. Do it as a team, do it together.”

At the colorful Water Cube in Beijing, Phelps led off the 4×100 free relay with an American record 47.51, although he was behind Australian Eamon Sullivan, who went out in a world-record 47.24. Then Garrett Weber-Gale gave Team USA the lead. Fred Bousquet of France overtook Cullen Jones on the third leg to give Bernard a half-second advantage for the final 100.

Bernard came into the Games as the world record holder in the 100m freestyle. Lezak was a half a body length behind the Frenchman when he dove in for the anchor leg. “He wasn’t just some chump,” Lezak said of Bernard, “so I had to swim pretty well.” Most considered the race to be over. “Jason Lezak is going to have to make up some ground on Alain Bernard, who stands six-feet-five and can absolutely fly,” said Dan Hicks, who was calling the event for NBC. “I just don’t think he can do it, Dan,” said three-time Olympic gold medalist and NBC analyst Rowdy Gaines, who is arguably the biggest USA Swimming “homer” on the planet. “I mean, Jason Lezak has been there…But I – I just don’t think he can do it.” Even Lezak had doubts, admitting after the race he really didn’t think he could catch Bernard. Yet he did.

Although the 32-year-old Lezak was about three-quarters of a second behind at the turn, he found another gear, drawing even with the fading Frenchman with ten meters left. With Phelps and Weber-Gale on the blocks screaming Lezak on, the captain barreled to the finish, out-touching Bernard to win by .08 of a second. It was the fastest race in history. The Americans shattered the world record they’d set in the prelims the night before by four seconds! In fact, each of the top five teams all bettered the one-day-old world mark.

Lezak’s anchor leg in Beijing was voted “Best Moment” at the 2009 ESPYs.

The win not only gave Team USA its first gold in the event since 1996, but it also kept Phelps’ hopes for eight gold medals alive, as this was only his second event in his quest to surpass Spitz. Jason Lezak went 46.06 – the fastest relay split in history, and more than a full second faster than Sullivan’s 47.24. However, swimming’s governing body, FINA, does not recognize world records for relay splits, unless they were in the opening leg, because only the opening leg is done from a stationary start.

Although Lezak considered retiring after Beijing, he came back in 2012 where he was again, at 36, the oldest swimmer on the American team. The wily veteran won a silver – his eighth and final career Olympic medal — by anchoring Team USA in the prelims of the 4×100 free. Five months later, Lezak retired from competitive swimming.

Since 1938, the 4x100m freestyle relay world record has been lowered 31 times. Americans own all but five of them, including the last three in a row. Jason Lezak has anchored the relay on two of those three. The 3:08.24 mark set by Team USA at the 2008 Olympics remains the world record, and is second only to Phelps performance in the 400 IM – set in Beijing one day earlier – as the oldest record in men’s swimming.

A new expression joined the swimming lexicon during the 2008 Olympics. To get overtaken at the end of a relay has come to be known as being Lezaked.

It has been over 11 years since The Split – the greatest come-from-behind, never-say-die relay leg in history at the 2008 Beijing Olympics. It was 46.06 seconds of pure inspiration, the most epic swim relay finish of all time. Lezak has watched it “a million times” [give or take a few hundred thousand] and never tires of the ending. “Whenever I watch it,” said the clutch Californian who remains an inspiration to young American swimmers everywhere, “I still get pumped up.”

Now 44, Jason Lezak lives with his wife, Danielle, who swam for Mexico in the Pan Am Games. The couple, who have three children and a lab named Bailey, make their home in southern California where Jason is an account rep for Adidas Swim. This past spring, Jason Lezak was inducted into the International Swimming Hall of Fame.

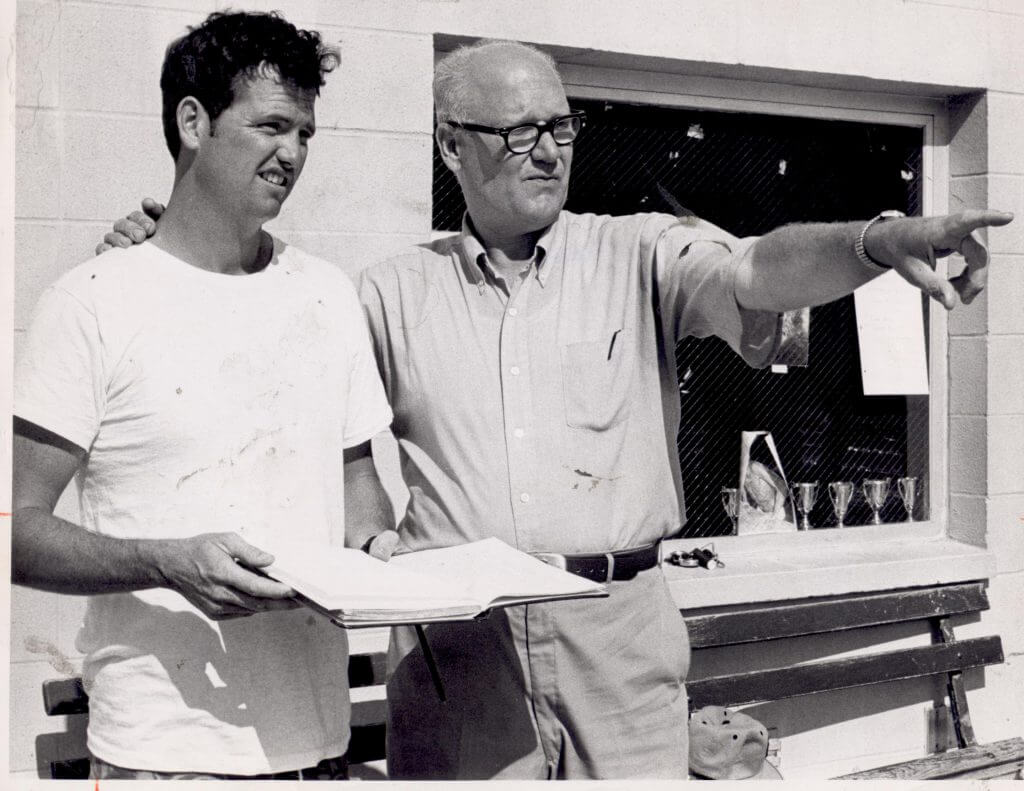

On this date in 1964, Americans Steve Clark, Mike Austin, Gary Illman, and Don Schollander lowered the world record in the 4 x 100-meter freestyle relay at the Tokyo Olympics, going 3:33.2. Clark’s leadoff leg of 52.9 shattered the world record in the 100. Swimming anchor, Schollander captured his fourth gold medal of the games, at the time the most medals won by an American since Jesse Owens in 1936. The 1964 U.S. men’s team broke the previous world record by nearly three seconds, and their mark stood until August 1967.